Usually I walk into the theaters with a vague sense of what is going to happen on stage. Nassim, though, was very different: the actor, the audience, and I all had not even a vague concept of what’s coming.

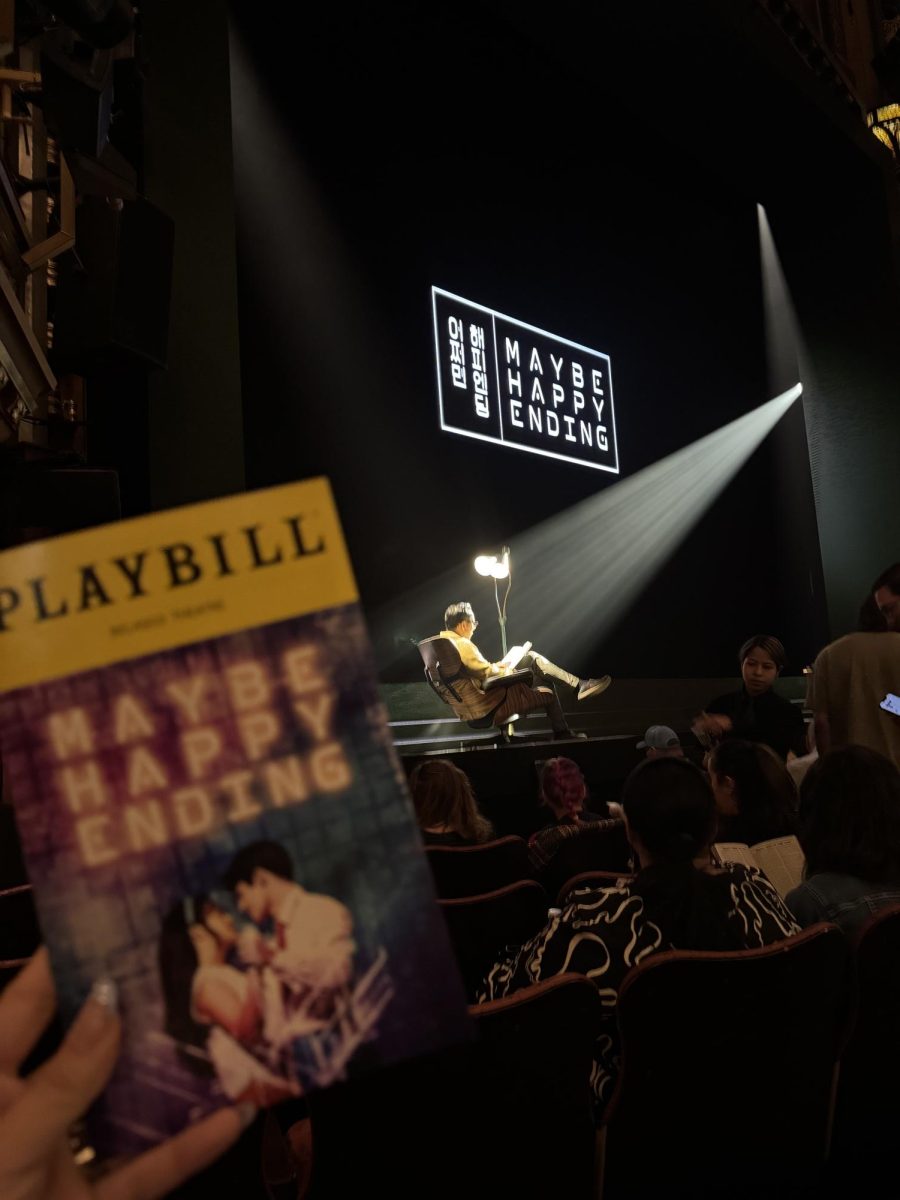

In each performance of Nassim, there is a different actor: at the Huntington, they are usually renowned artists from the Greater Boston area. On the night of October 25th, I sat down on my seat in the orchestra and saw a box with the actor’s name–Tony Estrella–written on it, lying on a table at the Huntington Calderwood Pavilion stage.

A script that only Nassim Soleimanpour–the playwright–knows is sealed in it. As the show starts, the production team opens the box and hands a stack of notecard-sized script pages to Estrella.

Immediately, the script was projected onto the screen where the audience can see the text as Estrella reads the words out loud.

Eventually, we got used to this unique but simple form of communication between us and the playwright, who is still trying to learn English with every performance in the United States. He is holding the scripts and using the words on it to talk to us through Estrella’s voice.

Later, we realized that Nassim, the playwright, was projecting from the back of the stage. He shares tea with Estrella before revealing himself to the house and continues communicating with us through a projected screen.

He continued telling his story: “Yaki bood, Yaki nabood”–once upon a time. Nassim’s mother named him as it meant the soft breeze, and she knew that Nassim would grow to become someone great and she couldn’t constrain him.

Nassim ended up translating his play to over 40 languages and performed thousands of shows around the world, except for in his homeland, Iran, in his mother tongue Farsi. He has attempted to translate the play for his only possible audience–his mother, but realized how hard it was. Through the play’s humorous play on languages, Nassim slowly taught Estrella–and all of us in the audience–how to speak some words in Farsi.

After asking the audience to take something out of their pockets as a souvenir gift to Nassim as he continues his journey to different cities around the world. Some took out green-line tickets, keychains, a 20-dollar bill, and a half-finished subway sandwich. He keeps these gifts as a souvenir of his travels, and a memory that will last very long.

At the end of the show, Nassim called his mother, one of the most important motivations and elements for his play. With the guidance of Nassim, Estrella spoke to her in Farsi, now a language that everyone in the house can comprehend a little.

Nassim is using the power of his play to reach something bigger: to bring the play in Farsi to his mother, but with actors of different backgrounds and who speak different languages to play it, and to show the power of language to both separate and bring us together.

Nassim is far different from the conventional structures of a play. There are no rehearsals, no significant sets, very few props, and barely any changes in lighting throughout the show. But the message remains clear, and the show never ceased to entertain every minute.

Contrary to my initial expectation, I ended up laughing so much with others in the house, as if we were all old friends of Nassim and Estrella–even though we all speak different languages and carry different identities.

It is highly experimental but also extremely successful in conveying its message to the audiences, without ever having to speak the same language or experiencing similar things. The arts, languages, and experiences can always be shared between any humans.

Just like Nassim said at the end, “no matter which language, ‘Mumun’ always means home.”