On March 11, 2011, an earthquake measuring 9.0 on the Richter scale struck near Fukushima, Japan.

When the first wave of the earthquake hit, the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant lost all external power supply, and the ensuing 14-meter tsunami penetrated deep inside the plant, completely destroying all AC and DC power supplies. Without a working operating system, hydrogen explosions occurred one after another in the fuel plants of Units 1, 3, and 4.

To prevent further deterioration of the situation, Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) urgently injected seawater into the unit cores. This prevented the destruction of the entire plant and the surrounding area. However, radioactive gasses were still being released into the atmosphere. On April 12, 2011, the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency of Japan classified the Fukushima nuclear accident as a Level 7, the highest level of nuclear accidents—a mega accident—the same level as the Chernobyl accident.

The seawater injected into the reactors did not mysteriously disappear. Instead, it became dangerous nuclear wastewater in the reactors. In March 2012, TEPCO took the first measurements of the composition and concentration of radioactive substances contained in the nuclear contaminated water. At that time, the results showed that there were as many as 64 radioactive elements whose concentrations exceeded the standard. In addition to the radioactive elements commonly found in nuclear power plant wastewater, there were also additional radioactive substances such as plutonium, strontium, cesium and other trans-uranic radioactive substances.

However, on April 13, 2021, the Japanese government officially decided to discharge millions of tons of contaminated water from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the sea. TEPCO claims to have invented the Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS). ALPS reduces all 62 nuclear substances in the contaminated water below international standards and dilutes the only remaining radioactive substance, tritium. However, this initiative still places the safety of the marine environment in an extremely precarious position and has the potential to cause irreversible damage.

If the radioactive substances of nuclear wastewater entering the oceans are dispersed and their concentration increases, stimulating marine plants, plankton, benthic organisms and fish, which are more sensitive, it will have an impact on the species diversity and ecological balance of the marine ecosystem.

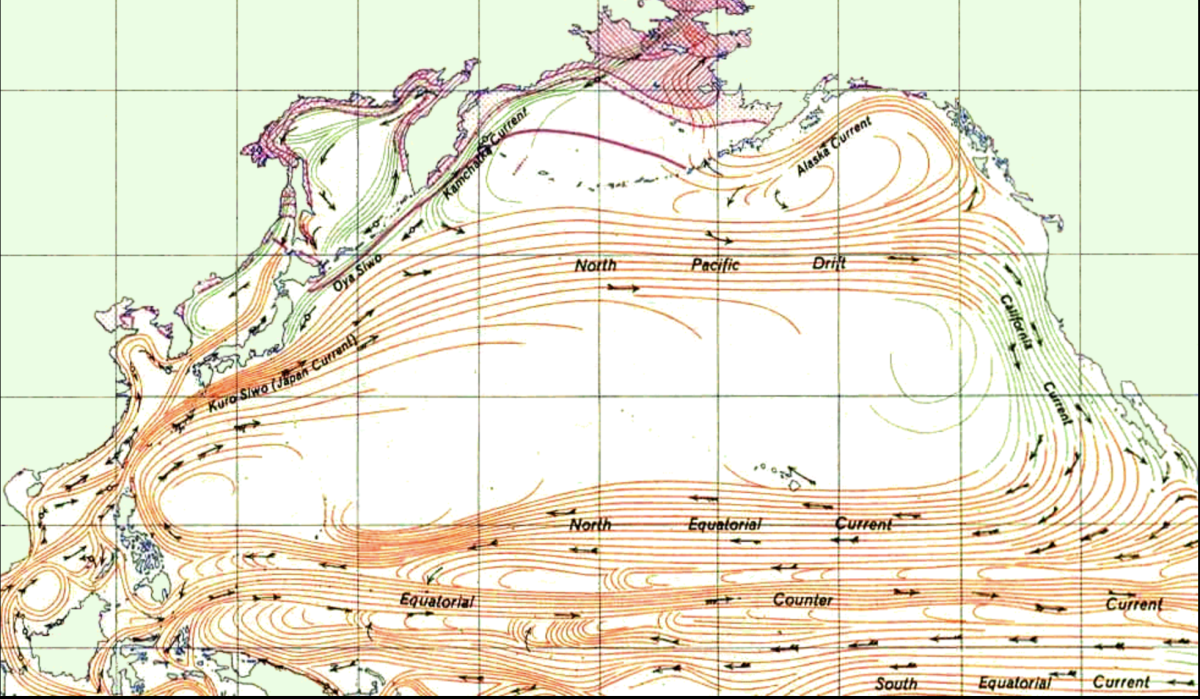

At the same time, given that nuclear wastewater does not remain in one place, the discharge of nuclear wastewater may lead to the spread of pollutants in the environment. This may affect the water quality and ecosystems of the surrounding seas and have an impact on activities such as fisheries and ecotourism in neighboring areas. Along with the Pacific Rim currents, the nuclear wastewater injected into the ocean at Fukushima will most likely spread along the coastlines of the United States, China, and other countries within a year, seriously affecting the international marine ecosystem.

Even more frightening is that the radioactive substances in the nuclear wastewater will spread through the food chain. If humans eat seafood affected by radiation, they will ingest radioactive substances. For example, iodine-129 is a radioactive substance that emits low-energy beta and gamma rays with a half-life of 15.7 million years. It can be absorbed by the thyroid gland and cause thyroid cancer and thyroid dysfunction. Plutonium-2394 is a radioactive material that emits high energy alpha rays with a half-life of 24,100 years. It can be absorbed by the lungs, liver, bones and other organs, leading to lung cancer, liver cancer, bone cancer and so on.

And while people’s attention is drawn to the 64 radioactive elements reported, it is easy to overlook the fact that there are still some potentially dangerous substances that have not been detected.

As an example, Mitsuko Amano, a researcher at the Japan Atomic Energy Agency, says, “Tellurium is as toxic as potassium cyanide, but TEPCO has not mentioned tellurium at all, nor has the Nuclear Regulation Authority. There are tens of kilograms of tellurium in the nuclear fuel residue, and I think it’s a very dangerous thing.”

Even after the so-called filtration process, the risk remains. When the South Korean government’s Fukushima Nuclear Wastewater Treatment Facility Mission went on a field trip to Japan in May 2022, it was informed that the Fukushima plant’s ALPS had experienced eight failures between 2013 and 2022, including equipment corrosion and equipment filter failures. And in June of the same year, 2 tons of treated nuclear-contaminated water leaked from its storage tanks. Although it did not flow to the outside, higher-than-normal concentrations of radioactive substances were detected in rainwater around the storage tank.

The first batch of discharges, which began on August 24, totaled 7,800 tons of treated nuclear contaminated water, according to TEPCO. And before the start of the official discharge, Fukushima nuclear contaminated water has been stored to 1.3 million tons, the entire discharge process will take at least 30 years.

Continuous discharge for 30 years requires continuous and close supervision. Even the most authoritative organization, even the most rigorous process, is still a human operation. And the possibility of operational error remains unknown. The active discharge of nuclear wastewater into the ocean is a highly controversial and potentially dangerous endeavor. It remains to be seen whether Fukushima’s nuclear wastewater will destroy the entire marine ecosystem.