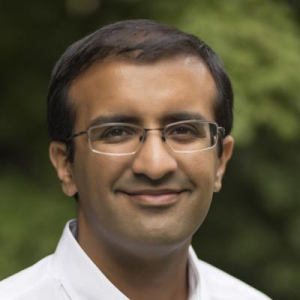

Addressing a packed Ruth Corkin Theatre as the keynote speaker for the 15th Annual Grogan Humanities Symposium, Dr. Rajesh Panjabi recalled growing up in Liberia, his home country, which experienced a civil war in 1989.

“One percent of the country controlled 70 percent of the country’s wealth,” he said. “The country had ignored education for rural people and indigenous people. The very people who had been living there for generations and centuries. Eventually, this led to violence.”

The war began in the countryside, and within months the rebel armies approached his hometown in Monrovia, the nation’s capital. He mother knocked on his door, saying, “Raj, pack your things, we have to go.” The rebels had captured the only international airport, forcing his family to a makeshift evacuation area. Eventually, Dr. Panjabi and his family were thrust into the cargo compartment of a rescue plane.

“We were sitting on a bench, a wooden bench. There was the luggage right in front of us with a big net cast over it,” Dr. Panjabi said. “My heart was racing as a nine-year-old as you can imagine. My dad had been trying to help others get out. I looked out across the open hatch, the hatch through which we had entered the back of the plane. I saw hundreds of others. People that don’t look like me. My parents had immigrated to Liberia. People who had been native born, had had heritage from Liberia.”

About 15 years after settling in North Carolina, the memory of that day had not escaped Panjabi’s mind. Now 24, he had received his green card and had the chance to return to Liberia, to see how he could serve the people he and his family had left behind.

He found utter destruction. His primary school had been destroyed, street lights demolished, and there was no running water.

“Worst of all was the human loss,” Panjabi said.“We had lost about a quarter million of our people, a country of only five million. Everyone had been affected by this conflict. We were also left.

As a medical student, Panjabi was interested in healthcare, and he was astonished to learn that just 51 doctors were serving a country of five million

“To put that in perspective, imagine the entire city of Boston having just eight doctors to care for everyone with a sore throat,” Panjabi said. “To care for everyone with a heart attack. To care for everyone who is trying to give birth. That’s a tough thing to do. When I got involved in the healthcare system as a volunteer, I was put into remote rural areas.”

Volunteering in remote areas, Panjabi saw patients die from conditions that are commonly diagnosed, and that “nobody should die from in the 21stcentury,” he said. This includes complications of child birth, to simple things like strep throat and pneumonia.

“It turned out that a billion people on this earth, about a seventh of the planet go their entire lives without seeing a professional health worker,” Dr. Panjabi said. “They live without access to these areas. What I was realizing is that illness is universal. Healthcare is not. This lit a fire in my soul. No one should die, because they live too far from a doctor. No condition should be permanent.”

This got Dr. Panjabi thinking. What if he could train people in remote areas to diagnose and treat common ailments? That’s just what Panjabi did, when he used $6,000 from his wedding in 2007 to start a nonprofit organization, now called Last Mile Health.

“We tried to invest…in the people closest to the problems we want to solve,” Dr. Panjabi said. “Making them part of our teams is absolutely vital to our goals of public service, of health equity, of social justice. What a doctor could do in four years, we carved that out. Instead of 4,000 things, a [team member] would be doing 30 things.”

Thanks in large part to Dr. Panjabi’s efforts, these community health workers, working alongside doctors and nurses, now help to ensure that the kind of care that a primary care physician might provide reaches the places family doctors would never go.

Before ending his talk, Dr. Panjabi, now an Associate Physician in the Division of Global Health Equity at Harvard Medical School, a past recipient of the Skoll Award for Social Entrepreneurship, the TED Prize, and the Global Citizen Movement Award, and one of TIME’s 2017 “100 Most Influential People,” left the audience with one final insight.

“Illness is universal, access to healthcare is not,” he said. “I think it’s time, working all together, for us to change this condition. No condition is permanent—something my father said, it’s something I believe, and I think we can get it done.”

Transcript of Dr. Panjabi’s Address

[googleapps domain=”docs” dir=”document/d/e/2PACX-1vQPX-MrBRKmDHh6SUfNZYb4epMfvxojCz7bsORK6qtQCBY1qrQyX99vuRhkmtAkBhxa92r-NDwgNhcm/pub” query=”embedded=true” /]