Grade Inflation at Private Schools

March 6, 2019

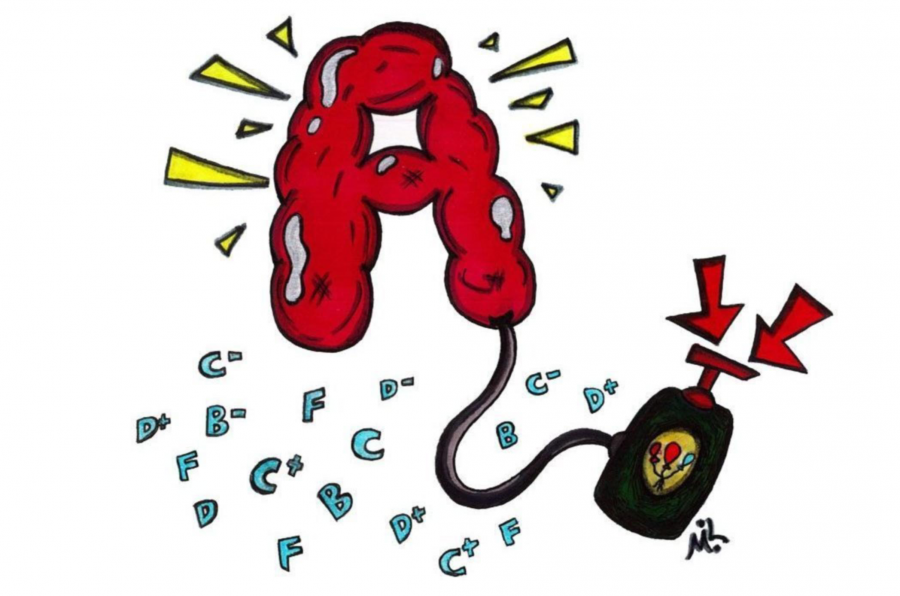

From 1998-2016, grade point averages (GPAs) at independent schools increased by 8 percent, compared to the 6.4 percent increase at private religious schools, 2.4 percent at suburban public schools, and .6 percent at urban public schools, a recent Education Week article reported.

This begs the question: are independent school students earning high grades because they truly earned them, or is something else going on?

Private schools, “to be attractive to parents, need to be able to tout how many of their students went to selective colleges,” Richard Weissbourd, who directs the Human Development and Psychology program at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, told The Hechinger Report in mid-August. “They’re incentivized to give better grades.”

The median tuition to attend a private high school in New England is $42,850, according to data collected by the National Association of Independent Schools.

Schools offer financial aid—here, 38 percent of Upper School students receive financial aid, with $34,232 the average amount awarded, according to Brimmer and May’s website—but families who don’t qualify are left with a big price tag. Next fall, tuition here will be $51,500, comparable to other independent schools in the area.

Assistant Head of Academic Affairs Joe Iuliano disagrees with Weissbourd, at least where the School is concerned.

“I do not think there is any correlation between tuition and grades,” Iuliano said. “I think there’s probably a better correlation between the student and grades.”

Other administrators feel similarly. Grade inflation must be put in perspective, especially at self-selecting independent schools, according to Upper School Head Joshua Neudel.

“There is a high percentage of students at independent schools who are academically driven. Statistically, these students tend to work harder and take advantage of all the opportunities that they are presented with at school, which leads to higher grades. Given the small class sizes at school like Brimmer, students are set up for success, as opposed to students that may go unseen at larger schools. To me, this is a complex statistical model and I would want to see how all the data is charted before I formed a stronger opinion.”

The “Class of 2019 Profile,” which the School composes to send to colleges and universities, reveals that “A” was the most common grade earned during the graduating classes’ junior year, followed by “A-,” “B+,” “B,” and “B-.” Of 300 letter grades reported, 29 were “C+” or below.

Students are mixed over grade inflation here.

“Grade inflation happens, and it’s not fair,” Sita Alomran said, referring specifically to senior year. “Some students study really hard and deserve the high grade. But some teachers are too lenient, and that lessens the value of the hard work that students put in.”

According to Mark Donato ‘19, grade inflation exists, but it depends on the course and the teacher.

“But with some classes, there is generous leeway with the grade, which is not an accurate representation of the performance,” he said.

At the same time, Donato says that with shorter marking periods, especially for seniors, the grade may not be an accurate representation of a student’s performance, in which case he appreciates more generous grading.

However, not all students feel as if grade inflation is a concern.

“I work really hard for my grades, and that work shows in my progress reports,” William Apostolica ’20 said. “I think all of my teachers, especially this year, are extremely fair. They are not overly generous. You have to really work for your grades.”

“All of my teachers are pretty fair with their grading, and I haven’t seen too much grade inflation,” Lily Goodman ’22 said. “I earn what I think is a fair grade.”

Humanities Department Co-Chair Kelly Neely said that she encourages students to see themselves as making progress from one point to another, no matter the letter grade.

“What matters is that you’re seeing improvements in yourself and your understanding of the material,” Neely said.

When she became Head of School in 2012, Judith Guild rethought how to offer support to students who hit a plateau in their learning.

“Success is often about progress and rebounding through difficulties. Students can now receive help in the library, help online, human resources are more available, and peers are seen as a solution to needing help with learning,” Guild said. “If that results in a better grade, then I am all for it. A higher grade should not be a result of pure effort but of improved knowledge and skill.”

Inflation is also hard to measure, according to Guild.

“In our country, a ninth-grade English class at one school looks quite different than those at other schools, private or public,” Guild said. “Therefore, a measure of grade inflation is quite subjective. It is the trend line of performance that tells a story. So, I ask, are the GPAs going up because students have more resources for support? Think about how using online tutorials have changed performance. Look at how students seek help at Brimmer, so they can achieve at a higher rate. Maybe those qualities are the actual variables that move a grade up and not inflation. It’s hard to know.”

What remains controversial is whether this means one school type is better than another.

In 2013, researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign wrote a controversial book, The Public School Advantage: Why Public Schools Outperform Private Schools, which argues that “after correcting for demographics, gains in student achievement at public schools are at least as great and often greater than those at private ones.”

Still, students at independent schools continue to have higher cumulative GPAs.