Op-Ed: Reflecting on My Cultural Identity

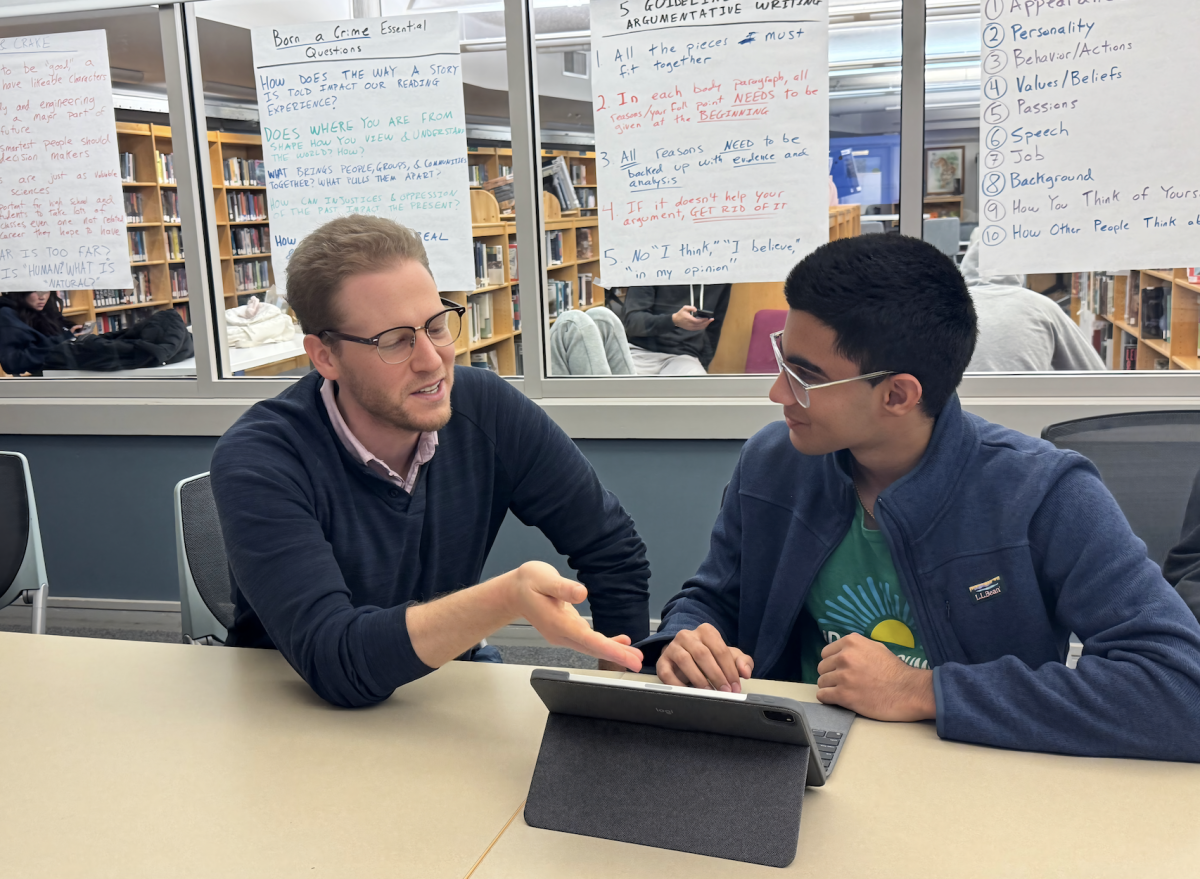

Kozhemiakin looks in the mirror. Photo Illustration by Edan Zinn ’23.

October 9, 2020

From the time I was very young, I have been heavily immersed in my culture.

Сырники (tvorog pancakes) on Sunday mornings is the thing I look forward to the most, in particular.

The luscious, buttery taste of the Russian cheese pancakes and bitterness of blackcurrant is a taste that will be forever ingrained in my mind. Its scent lingers throughout the house and into my room, serving as an alarm clock to remind me to wake for breakfast.

This is a typical Sunday morning, with my father preparing the traditional Russian Сырники recipe, derived from his grandmother.

In the evenings, I return to the spices of Puerto Rico.

The aromatic perfume of ocean waves and rainforest dew, exclusive to the island, is one that cannot be replicated, but instead replaced by guava pastries and tres leches in our own kitchen.

Food is just one of the many ways my culture lives on every day.

I hold both my Russian and Puerto Rican cultures close to my heart, but when a question like, “What is your background?” is posed, I begin to question my identity.

It all comes down to figuring out where I belong.

When considering my identity, I tend to view it through two lenses—Russian and Puerto Rican.

I seldom encounter struggles with my Russian identity because of how seamlessly I fit into the stereotypical image of a young Russian-American female. I am, after all, a pre-professional ballet dancer who plays piano and has a deep passion for classical music.

To top it all off, I appear much more Russian than Hispanic.

A lack of Hispanic features is what puzzles most people when I mention that I am Puerto Rican.

As if others are denying a substantial part of my family’s history, the most common response is “but you do not look like it,” or “are you actually Puerto Rican?” This type of questioning can be quite offensive, even as most don’t realize the effect of their words.

This is why identifying as Puerto Rican, while appearing predominantly Russian, has always been difficult for me

My mother, Jennifer Kozhemiakin, feels similarly.

“Having red hair and fair skin, others often laugh when I mention that I am Puerto Rican. It had shaped me from very early on because I learned that you cannot assume someone’s background solely on the basis of their hair color or skin color. That’s a dangerous thing to do,” she shared.

My grandfather, Joseph Alemany, also shared his experiences as a Puerto Rican teenager in the 1940s, when he first came to the United States.

“I traveled alone by ship from San Juan to New York City (The Bronx, then referred to as Spanish Harlem),” Alemany said. “My mother and I later settled in Bayside where we lived in a rooming house and shared one tiny room. It was very, very hard. When we first came here we had very little money and there were times where the only thing we had to eat was a can of Campbell’s soup that we shared,” he continued.

When I asked about his experiences with racism and discrimination, he recounted several experiences from his childhood.

“In New York, around 1947, Puerto Ricans were not very well thought of. In school, my only friends were black; the whites would not talk to me. It took me a long time until I was accepted into the white community,” he said. “The schools were also very prejudiced. They changed my name from José Enrique to Joseph Henry without telling my mother. They also told my mother to never speak Spanish to me at home, and that is how I lost the language.”

My grandfather’s story is one that is deeply ingrained in our family’s history. When others question my background, I feel that they are questioning this history and my identity.

Although I do not live near my grandfather, I maintain a close connection to Puerto Rico by staying in touch with my many relatives on the island, and regularly incorporating Puerto Rican culture and traditions into my family’s daily life.

In contrast, the connection to my Russian culture is in part due to my father.

Growing up so close to him, watching Russian cartoons such as “Снежная королева” (The Snow Queen), attending the Russian rock concerts my father and I so greatly enjoyed, and making weekly trips to the Russian grocery store, shaped who I am.

Not to mention the times in which he would pick me up from ballet rehearsals and we would blast “Поворо́т” (Turn), one of our favorite Russian songs, through the open car windows.

My father, Dr. Alexander Kozhemiakin, left the Soviet Union just as he turned eighteen years old, not solely because of economic necessity but more importantly because he wanted to escape the stifling environment of the decaying communist regime and longed to see the world.

“Traveling freely abroad was an impossible dream when I was a child in the USSR. The regime was afraid to let its own people out as it feared and rightly so, that it would open up their minds, exposing them to new ideas, different ways of life. As the old saying goes, the world is a book and those that do not travel read only a page,” Dr. Kozhemiakin said.

My Russian and Puerto Rican identities are very different—literally a world apart. Some would say that they are like oil and water, they just do not mix. Yet, I believe that they do overlap and this is what truly defines who I am.

Both perspectives have taught me to keep my mind wide open, actively seek out new experiences, embrace diversity, and eschew biases.

I cling to these values, as I cope with today’s political environment characterized by rising intolerance towards people—both our own citizens and foreigners—who have a different skin color, socioeconomic status, or belief system.

After all, I believe that if we all chose to cling to these values, we will undoubtedly conceive a much more accepting, open, and diverse world, which is exactly what we need.