Op-Ed: My Greek New Years

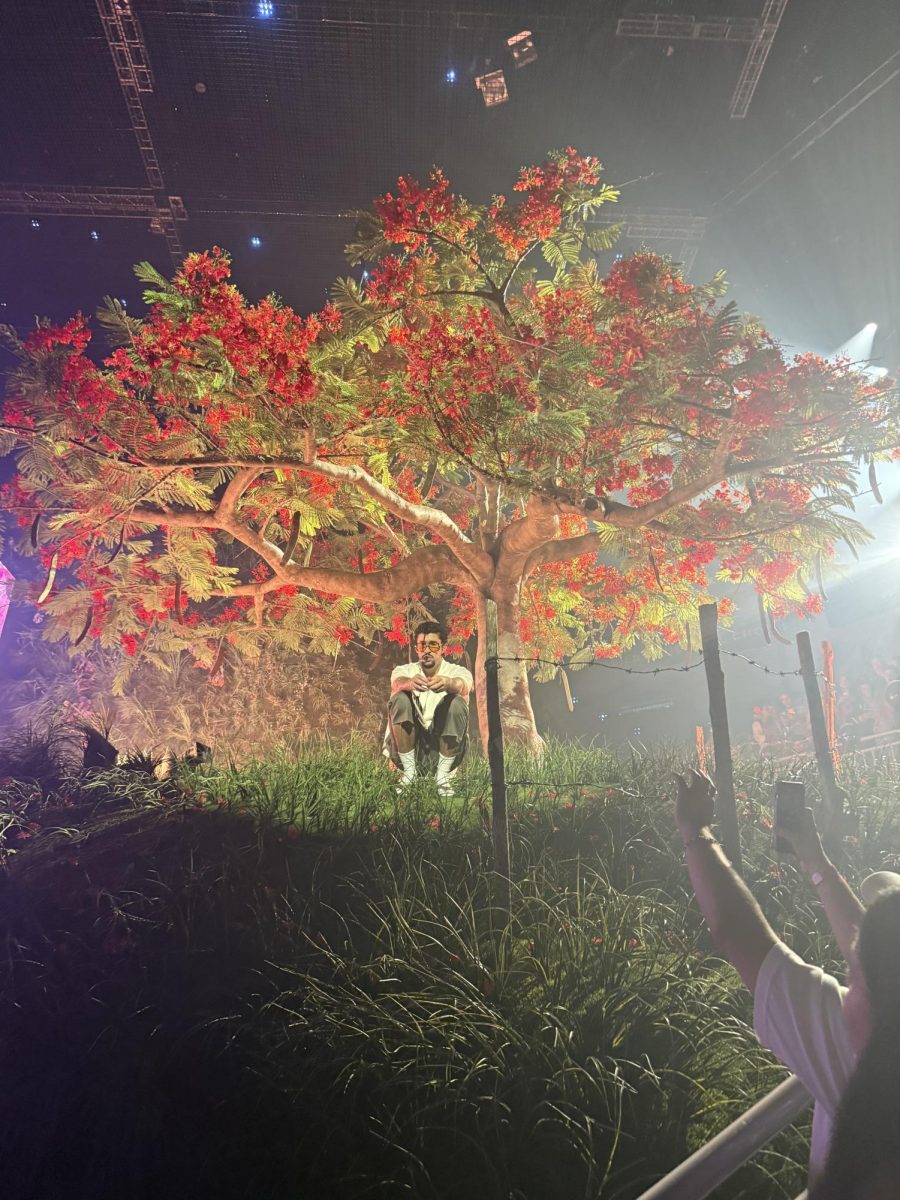

An orange cake that Papas’s grandmother and her housekeeper made. Photo courtesy of Grace Papas.

January 8, 2021

One of the things I’ll always remember is the smell of citrus and sugar that overwhelms my grandparents’ kitchen on New Year’s Day. The baking cake in the oven rises slowly, like the sun, and the counter is always powdered with flour and sugar, with orange peels strewn over the mess like flower petals.

That’s how I know that the new year has arrived.

As long as I can trace back, the tradition of the vasilopita has been carried in my family’s history. This Greek tradition is one near and dear to my heart, and close to many of my family members.

There are many traditions that Greeks have to ring in the new year. While my family and I don’t partake in all of them, they all have an important place in a Greek household. However, this particular event is one that I’ve taken part in ever since I was old enough to chew properly.

The tradition of the vasilopita goes all the way back to the 4th Century in Caesarea, Cappadocia, which was located in Asia Minor. The tradition was started by a bishop named Basil, who is now a well known saint and a very important part of Greek New Years celebrations.

St. Basil is the Greek version of Santa Claus, and during the New Year’s feasts, families always lay out an extra place setting for him.

The vasilopita tradition began with St. Basil wanting to donate money anonymously to the poor. He was struck with the idea to bake gold coins into loaves of sweetened bread, which even the poorest could afford. He then proposed the idea to the village bakers, and they agreed to help him and baked the money into hundreds of loaves.

So, when the needy families cut into their bread, they found many gold coins inside, buried in the dough. Less nourishing than bread, maybe, but even so, the families were overjoyed.

St. Basil’s fame spread quickly throughout the Byzantine world, and in honor of his many services to humanity and the Church, his Feast Day of January 1st became a day of Observance in the Orthodox church, and the tradition of cutting into a vasilopita every New Year’s Day was established.

Vasilopita, a Greek word, directly translates to “Bread of Basil” for that very reason.

This tradition is easily one of the things I look forward to the most during the holidays. The recipe comes from my grandparents’ housekeeper, who has been with our family for my entire life and to the point where she’s another grandmother to me.

Both she and my grandmother get to work the day before, baking a giant orange cake topped with a snowy layer of powdered sugar—a staple for Greek desserts— for our family, despite the fact that there’s never usually more than seven of us at the table.

That too is a part of being Greek, as I have learned.

The coin tradition has changed over the years. Instead of multiple coins for wealth, there is always one coin baked inside of the cake. It’s said that the coin will bring the person who finds it good luck for the year.

The cake, on New Year’s day, is divided into equal parts, with separate pieces cut for the House. Then, when everyone has their pieces, you have to poke your fork prongs into the citrusy cake, trying to see if you’re going to be the one with the coin, the one with good luck for the year.

And this year, it happened to be me.

Finding the coin is one of the things that excites me the most. I haven’t found it since I was nine, so I was thrilled. A little luck goes a long way, and I’m hoping to find that out for myself. I think I can speak for all of us when I say that I think we could all use a little good fortune this year, as well.

But the New Year is a time, regardless of culture, to leave misfortune and the past year behind. The best thing we can do, moving forward, is to keep our heads high and smiles bright, because that’s the way things start.

And for me, the new year begins with the smell of the vasilopita, the kitchen afterward, and the dull thud of metal on metal as you unearth that coin, hoping that it will serve you well going forward.