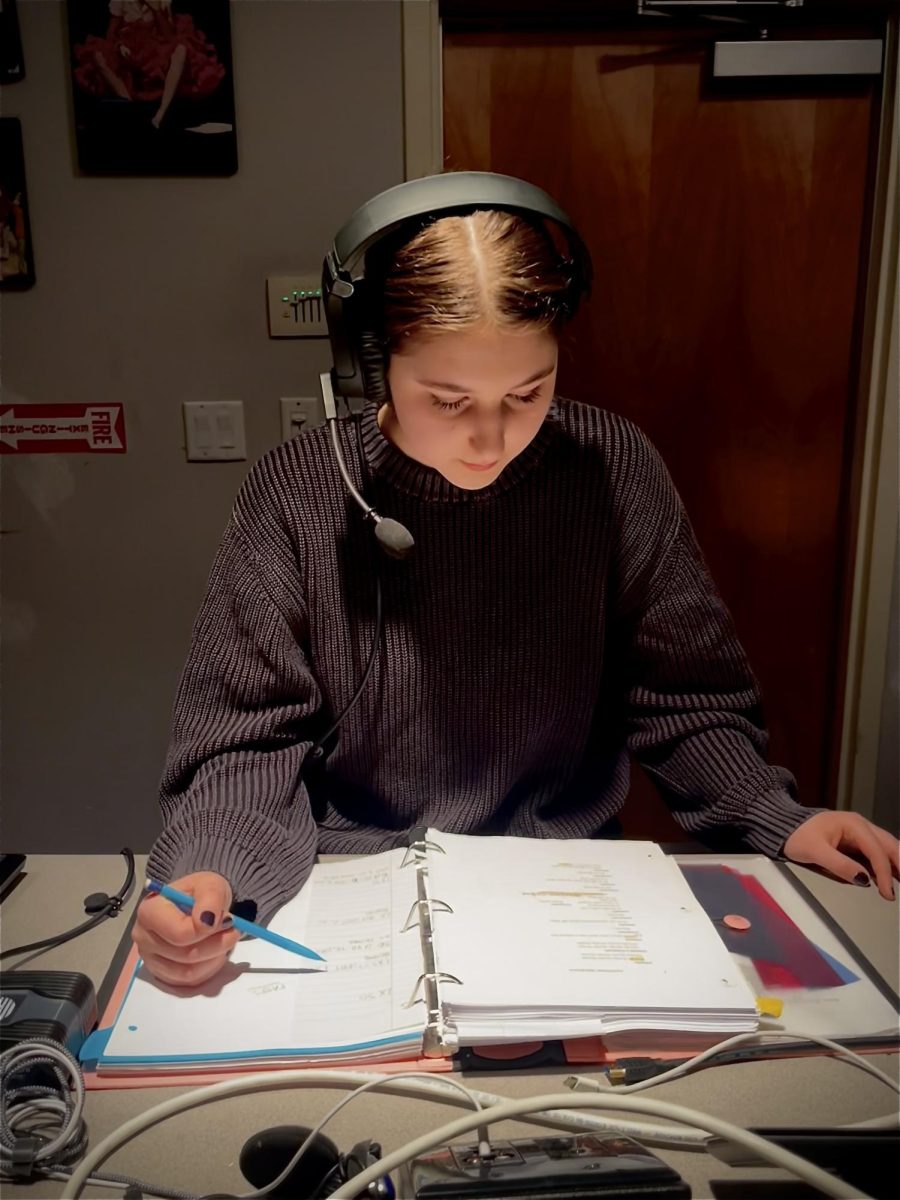

Guest Column: A Head Above the Rest

November 13, 2019

“Alexa, set an alarm for 4:20 am.”

Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday I wake up to an alarm that goes off way too early in the morning. No matter how much I want to go back to sleep, I quickly get ready.

My mom and I leave the house at 4:40 am and arrive at Community Rowing Inc. at 5:00 a.m. Practice is two hours long and we get out on the water no matter the weather. The cold air wakes me up and the quiet water is peaceful. I have been practicing three times a week for over a year to build my skills and earn a seat at the Head of the Charles, the largest and most difficult rowing head race in the world.

After long anticipation, I earned that seat, coxing for the Cornell Alumni Seniors Masters 4+, a boat of 4 male rowers over the age of 50. I’m responsible for steering the boat, and coordinating the power and rhythm of the rowers.

“Alexa, set an alarm for 6:30 am.”

I hear the alarm and I jump out of bed with excitement, get ready, and hop in the car. As we drive, I go over the three-mile course in my head, from the start at the Boston University boathouse all the way to the finish, 800 meters past the Elliot Bridge. I imagine how to steer every major turn and go through every bridge.

After we arrive, I walk inside and get my cox-box (microphone) and a bucket. I’m early, so I sit in the lobby waiting for my team to show up.

Once everyone arrives, it’s about 8:15 a.m. We go into the boathouse and start rigging the boat. I test my cox-box to ensure everyone can hear me. After the boat is rigged, we take it out of the boathouse and put it in slings outside.

At 9:30, we bring the boat down to the water.

We put the oars in the oarlocks and shove off from the dock, heading toward the start line three miles up river. Once we get past the Northeastern Boathouse, the river starts to get very crowded. It is as if we are sitting in bumper-to-bumper traffic on the highway. This is to be expected though with over 11,000 rowers from around the world. The traffic continues all the way to the start line.

Once there, we travel in a counterclockwise direction to line up in the chute. After a couple of minutes, the announcer states, “bow numbers 20 through 30 approach the start line.”

As I hear that, I tell my rowers, “All 4 sit ready from the release. Ready, all, row.” We slowly make our way to the start.

As 28 is called to row, I tell my rowers to sit ready. At last, the announcer says, “29 row at three-quarters pressure, increase to full pressure, you are on the course, have a good race.”

Mile 1

We are on the course. With the first stroke, I am jerked back and forth in the boat. The resulting bruises on my body are signs of a good race. My back faces the rowers and their backs face me. They row blindly, putting all their trust in me. I can feel that our rhythm is good and hearing the sound of the oars cutting through the water in unison reinforces this for me. I quickly gain confidence because I know I am doing my job well.

I tell my rowers to settle into a rhythm. As soon as we pass under the BU bridge, we start moving in on the boat in front of us. “We are lined up with their stern, pass me up two seats in the next five strokes,” I tell my rowers. “That’s 1, 2, 3—got one seat get me one more, 4, 5 and got it. Let’s finish them, walk away now.” Our adrenaline is spiking now. We’ve just picked off our first boat. I tell myself “baby steps, take it boat by boat.”

I move over toward shore to get the inside line in order to have the shortest course. A head race is all about time. Boats are released from the start in 20 second intervals, one after the other. The fastest time wins.

I see another boat in front of us and I am determined to pass them. I have to motivate my rowers to bear down and push harder. “Let’s pass this boat before the next bridge! Give me the pressure now!” I yell.

We pass the next boat in 10 strokes and beat them for the best line through the River Street Bridge. We continue through the bridge at a good pace, and within the next 20 strokes we are one mile into the race. I congratulate my rowers on our effort thus far and remind them the hardest part of the course is yet to come.

Mile 2

The next mile is crowded with boats all jocking for the best position to tackle the three bridges and two major turns. After the mile marker, we catch up with another boat and go through the Western Avenue Bridge side by side. My perspective is off because I am lying down and the jerking sometimes affects my vision. Because I can’t see behind me, I don’t know where my rower’s oars are in comparison to the other boat and bridge. I have to trust my bow seat to communicate with me. This is the part of the race I find most unsettling. I pray we don’t hit the bridge or lock oars. We successfully make it through. Again, I congratulate my rowers as we pass the boat.

Next up is the Weeks Foot Bridge. The advantage to being on my home river is that I know that I must steer the boat in a specific way to get through the bridge and immediately make the turn on the other side. I steer the boat wide toward the starboard side shore. My goal is to have a line that is perpendicular to the bridge. I ask for pressure from my starboard side to make us turn faster and assist with my steering. Another baby step accomplished. We successfully complete the turn.

To my disappointment, the boat we just passed has gained on us and is once again level, then ahead of us. My rowers also tell me that there is another competitor approaching from behind. I need to modify my strategy.

“Okay guys, there is a boat directly in front of us and directly behind us!” I yell. “Let’s keep this pace, but increase the pressure when I say.”

I wait to say “go” until we get our line through Anderson Bridge. In about 50 more strokes we pass the 2-mile mark and are in the home stretch.

Mile 3

We tackle the last mile, which includes one bridge and two difficult turns. Approaching the first turn, I have the best line, allowing my team to gain on two boats in front of us, which I push toward the starboard side shore, keeping my line. They follow proper race etiquette and move to the side.

We race perfectly through the Eliot Bridge. On the other side I see a boat in front of us which had passed us earlier in the race. My rowers are exhausted, and my voice is beginning to fail, but I want payback. I want to drive to the finish with everything that I and my rowers have left.

“Once we get around this turn, the finish line will be in site,” I tell my rowers. “There is a boat about two boat lengths in front of us. Let’s get around this turn and gain on them. Go hard now.”

We get around the turn smoothly and gain about one boat length. There is about 500 feet left in the race. We have bumped up our stroke rate from a 30 to a 32 and our speed has increased. I see the finish line and can’t believe that I am about to fulfill my dream of competing in the Head of the Charles.

“Come on guys, we are on the sprint!” I yell. “We are almost done with the race and the boat in front is now about half a boat length away. Let’s finish strong and get even with them in the next five strokes. That’s 1,2,3,4,5.”

With our bow on their stern, they pass the finish line first.

I am still excited and tell my boat to paddle.

“Great race, guys,” I say.

As we row home, I think to myself, “I just completed my first Head of the Charles with almost a perfect line, without running into a bridge or getting disqualified.” That’s a win in my book. I couldn’t be happier.