Op-Ed: Is Mastering a Foreign Language Worth It?

November 14, 2019

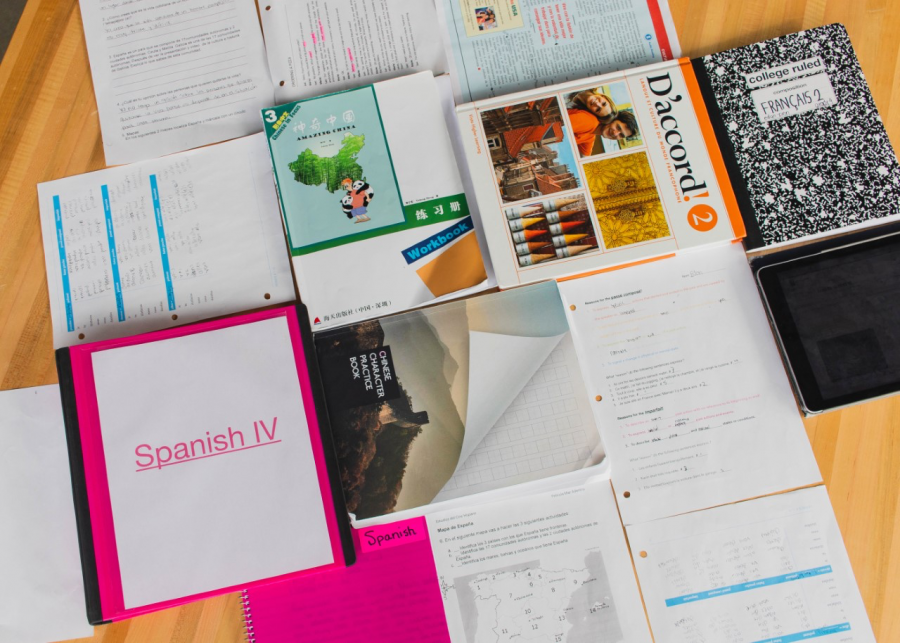

Should schools require students to take foreign languages?

For most, the answer is inevitably a resounding “yes.” However, further investigation sheds some interesting light on the question.

Although Massachusetts does not require a foreign language for students to graduate from public school, many cities, towns, and other states require at least two years of studying a foreign language to graduate.

Here, all students must complete at least three years.This requirement is similar to many other private schools in the Boston area. Both The Rivers School and Dexter Southfield require at least three years of a language to graduate.

It’s true that students with certain learning disabilities can receive language exemptions, but for others who struggle, the requirement can feel daunting and unnecessary—especially for those who feel that they want to enter a field where mastering a second language isn’t necessary.

Moreover, according to a recent Atlantic article, statistics show that less than one percent of students in the United States are fluent after taking foreign language classes in high school.

“That’s noteworthy considering that in 2008 almost all high schools in the country—93 percent—offered foreign languages, according to a national survey,” writes education reporter Amelia Friedman. “In many cases, as Richard Brecht, who oversees the University of Maryland’s Center for Advanced Study of Language, said on Thursday: ‘It isn’t that people don’t think language education important. It’s that they don’t think it’s possible.’”

Where schools require two years of language, students spend over three hours in a language classroom per week. Considering that there are about 36 weeks in the academic year, most students will spend over 216 hours in the classroom.

This is a lot of time to struggle to learn a language, especially if you are unlikely to become fluent.

To be fair, this isn’t just a problem in the United States.

A 2014 survey conducted by England’s The Guardian reveals that “almost eight out of 10 who have studied the most popular languages at school–including French and German–say they can do no more than understand basic phrases.”

One might argue that this merely shows the need for more investment in foreign language programs. But throwing money at any flawed system isn’t the solution. Massive spending would also be a waste.

According to a recent MIT study, mastering a foreign language only adds a 2-3 percent increase to one’s yearly earnings: Spanish by 1.7 percent, French by 2.7 percent, and German by 4 percent.

According to The Economics Student Society of Australia, housed at the University of Melbourne, “the only language with a much higher premium, around 10%-20%, is English. So for someone earning $70,000 a year, learning German could mean an extra $2,800 a year. At an individual level this may not seem large, but on a macro scale the difference is billions of dollars.”

I’m not suggesting that languages shouldn’t be taught in school. I think language classes teach critical thinking, patience, and respect for other cultures.

Rather, I advocate for altering foreign language requirements.

Schools should require students to fulfill two or three language credits, or a year to a year-and-a-half of study. That equates to roughly 126 hours, more than enough time to instill a working knowledge of a language, while also allowing learners to decide if they want to continue their studies.

Interestingly, some high schools across the nation are considering teaching computer science as an alternative to foreign languages. Computer science classes teach coding languages such as Python and Java, which also foster critical thinking, logic, and patience.

Lisette Titre, a game developer and education curriculum consultant, argues that coding “has the potential to make young people better writers and communicators.

In May of 2016, a bill passed in Florida that allows students to count computer science classes toward foreign language requirements. Texas passed a similar law in 2014, allowing students who perform poorly in a foreign language to take a computer science class as an alternative. That year, Georgia also passed a similar law.

Spanish teacher Mirna Goldberger believes that computer science and foreign languages are important, and she suggests that students learn both.

“It’s my opinion that it’s not only important to code, but it’s also important to know different world languages,” Goldberger said. “You can’t communicate in Java with somebody who is in Italy. Not only should you study how to code as a way to enter a globalized and industrialized economy, but you should also be able to communicate contextually at a cultural level. It’s not an issue of one versus another, but rather I think it’s an issue of how to invest in schools so that they have both.”

I agree with Goldberger. Individually, foreign languages and computer science are important, but when studied in tandem, the disciplines have the potential to open new opportunities for students.

Computer science teacher Jason Bock agrees.

“I think in some schools it makes sense to replace foreign language with computer science, but I think at Brimmer and a lot of other schools, the goal of learning a language is to look at it from a global perspective—being able to travel and talk with unique people, and computer science misses that,” he said.

Foreign language and computer science provide valuable and practical skills, but they are not for everyone. While introductory courses should be required, higher-level classes should be optional.