ACL Tear: Every Athlete’s Nightmare

October 6, 2014

As a high school senior, I play soccer at a very competitive level. I am currently going through the process of getting recruited to play soccer in college. Having played soccer most of my life, it is my passion. Basically I live, eat, and breath soccer. Unfortunately, this summer I suffered the traumatic and dreaded ACL tear, which is every soccer player’s worst nightmare. Thankfully, I had a successful surgery and am currently in the midst of the long and time-consuming process of rehabilitation, and looking forward to getting back out on the field as soon as possible.

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament, commonly known as the ACL, is the major ligament in the human knee. The ACL is essentially a small strip of cartilage that keeps the bones on either side of the knee connected. Without it, the knee is unable to cut, pivot, or make any kind of non-lateral movements.

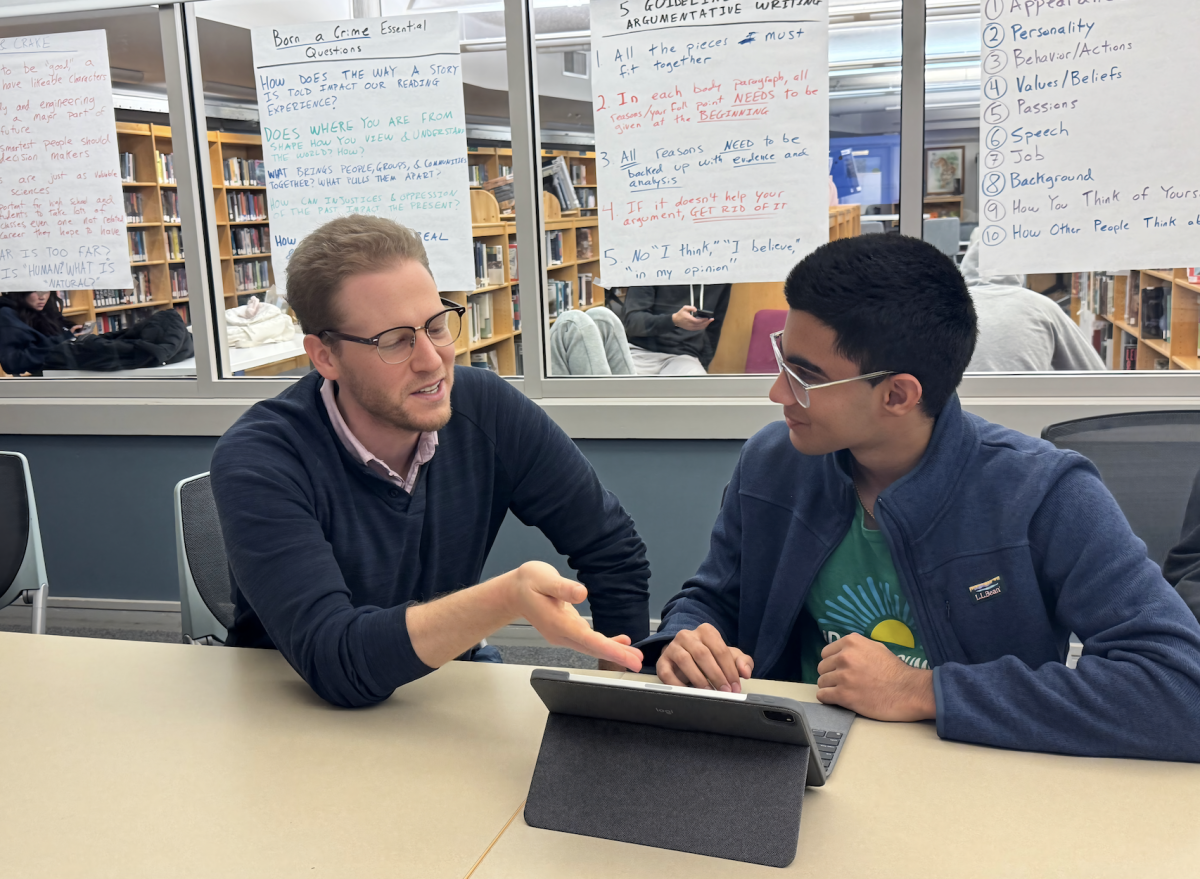

I spoke with Dr. Mininder Kocher, Associate Director of the Division of Sports Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital. Kocher is among the country’s most acclaimed pediatric ACL surgeons—and he also happened to be my surgeon.

“We’re seeing these injuries more frequently than we did before, and I think it’s because the kids are just playing at a much higher, competitive level at younger and younger ages,” said Kocher. “I’ve never seen an ACL tear in a kid playing kick-the-can in their back yard.” I learn from Kocher that more than ever, sports programs are pushing student-athletes hard. This suggests that a direct correlation between serious, adult level injuries and young people participating in aggressive, highly competitive athletic activities.

As a competitive athlete who grew up in this new world order, I’m a believer in performing to the best of my ability—and at the highest level of play. But since my ACL injury, I’ve acquired a new perspective on the competitive sports system for young adults. I have even begun to question whether it makes sense for young men and women to be participating at a level of play that heightens the risk of enduring such traumatic injuries, such as an ACL tear, that require major medical intervention and a long, painful recovery.

ACL tears are one of the most common knee injuries. In the US, there are over 100,000 ACL tears every year. They are most common among athletes, especially those who participate in soccer, basketball, or skiing—all sports that require the ACL to pivot, cut, land, or plant. In most cases, athletes that suffer a complete ACL tear must undergo reconstructive surgery if they wish to continue playing sports. This “involves harvesting ligaments from a perfectly healthy hamstring to rebuild the ACL. The surgery recovery takes an estimated 6 to 9 months varying with each patient.

Numerous studies confirm that women are more susceptible to this injury than men. More recent studies report that females are 4 to 8 times more likely to tear this ligament than males. Although there is no definitive reason for why this is the case, many doctors and surgeons believe it has something to do with structure of the female body in comparison to the male body.

Cristine Griffing, head athletic trainer at the Brimmer and May School, who has years of experience helping athletes through their post-surgical recovery, says, “The correlation between ACL injuries with women and girls is no coincidence. It is all related to the anatomical structure of the female body. Girls tend to have wider hips than boys, making their legs less straight and their knees more at risk when they are cutting or pivoting.”

So since this injury is so common, why can’t we find a way to prevent athletes from experiencing it? That was certainly my initial question after I getting the news about my injury. While there have been great advances in medicine and technology, enabling surgeons to rebuild this ligament more easily, I can’t help but wonder why the medical community hasn’t found a way to prevent the injury—or at least to minimize the number of athletes that experience ACL damage.

Studies indicate that doctors have been searching for a treatment that will allow the ACL to heal itself without surgery. A few experts believe that the frequency of this injury could be reduced if coaches would dedicate more time to the basics of the sport (balance, planting, finesse). Players must be taught how to stay solid and stable on the playing field before there can be any meaningful reduction in the “ACL epidemic.” Kocher says, “It is very difficult to have such a common injury with no clear, favorable treatment.”

I hope that by the time my child reaches the age and level where his or her knees will be susceptible to this injury, someone will have found a way to prevent or treat it more efficiently.