Op-Ed: The Dying State of Private School Media

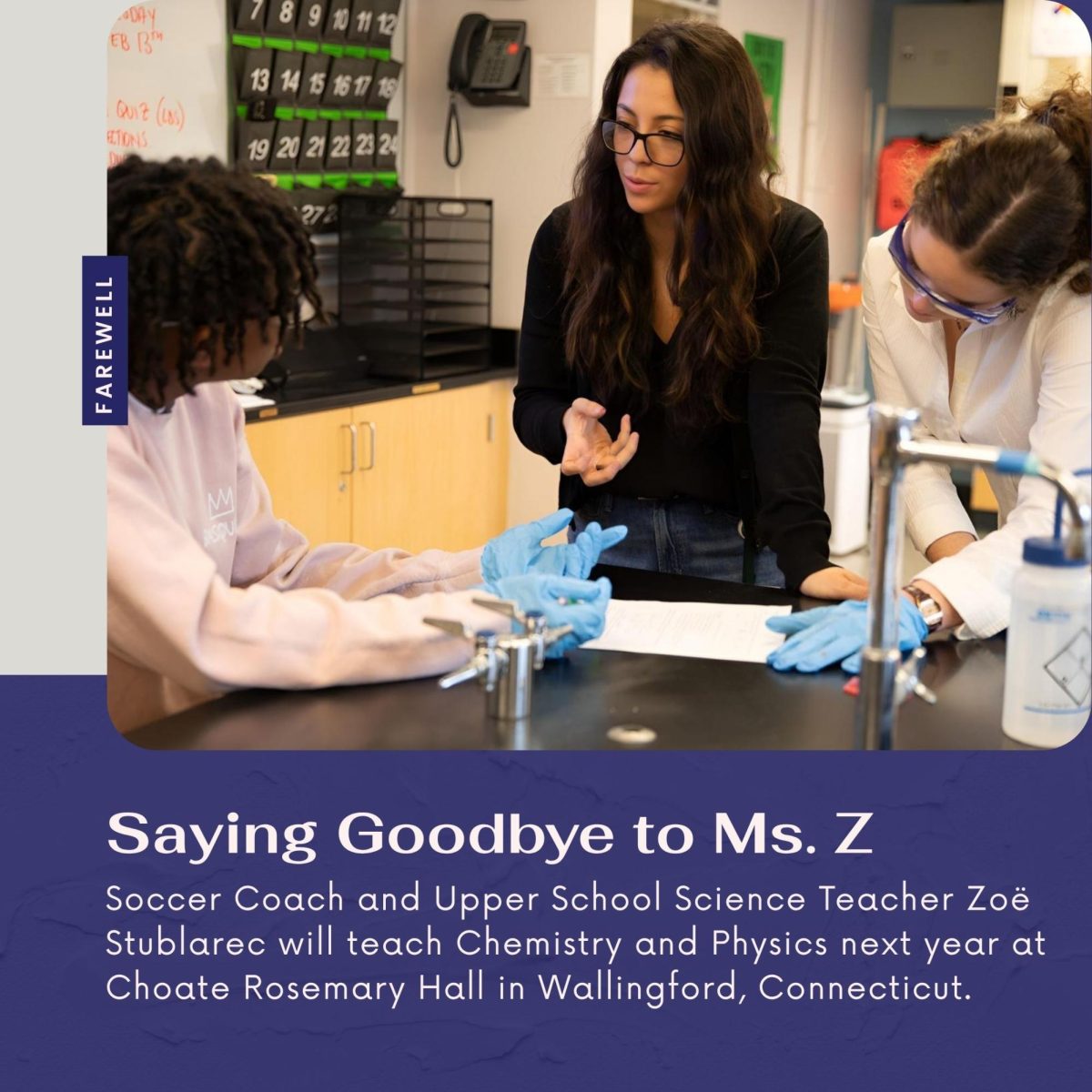

David Cutler presents about the lack of private school journalism at the 2019 Columbia Scholastic Press Association. Photo courtesy of The Feather Online.

December 9, 2020

Beyond a handful of the nation’s most prestigious and oldest independent schools, too few independent schools offer journalism programs or foster student publications. Where they do exist, they are likely to be on life support. This is a shame, especially because of journalism’s increasing centrality to everything that private schools hold dear about education, not the least of which is equipping young minds with skills to succeed after graduation.

Communications Professor Erica Salkin, author of Private Schools and Student Media: Supporting Mission, Students, and Community, put it this way when we spoke last summer:

“There are schools that don’t understand the valuable role that student publications can have in student development—in the development of voice, the development of identity, the ability to engage a public, to understand community issues,” she said.

“There is so much documented benefit to working on student press that, unless your mission is, ‘We don’t want to teach, and we want them to come out incredibly compliant,’ you cannot claim that you’re living by your mission statement [unless you support student journalism].”

Helen Smith, who serves as executive director of New England Scholastic Press Association, told me that membership in the organization, which costs $50 a year and provides invaluable student and adviser support, usually includes fewer than a dozen independent schools, in contrast with 70 or so public schools.

I also reached out to Carney Sandoe & Associates, the largest teacher-placement organization for independent schools. According to Julie Landis, director of communications, in the past decade, only three to five journalism teaching jobs have been listed with the company per year.

“In our opinion, a job like that is often not listed externally,” Landis wrote me. “Instead, a current English teacher might take on such a role, so we might not see the full picture. It is indeed still quite a small number.”

Here are the top three concerns that keep private schools from supporting scholastic journalism:

- Bad press. When full tuition costs as much as a luxury car, image is important. Administrators may fear the appearance of clumsy or seemingly trivial work by beginning journalism students, and they may not want to deal with growing pains. An opinion piece about a lack of snack options during break may also not be worth the risk of dissuading potential applicants. I maintain that supporting student voice, even on controversial issues, is far more important.

- Lack of resources. Even with a high price tag, schools, especially those with low endowments, are heavily tuition dependent. When every dollar is stretched, backing a student publication may not seem justified. If that’s the case, go completely digital. A yearly subscription option to WordPress, the industry standard among website-construction software services, is $300, which includes access to live-chat support for schools with questions about settings or controls.

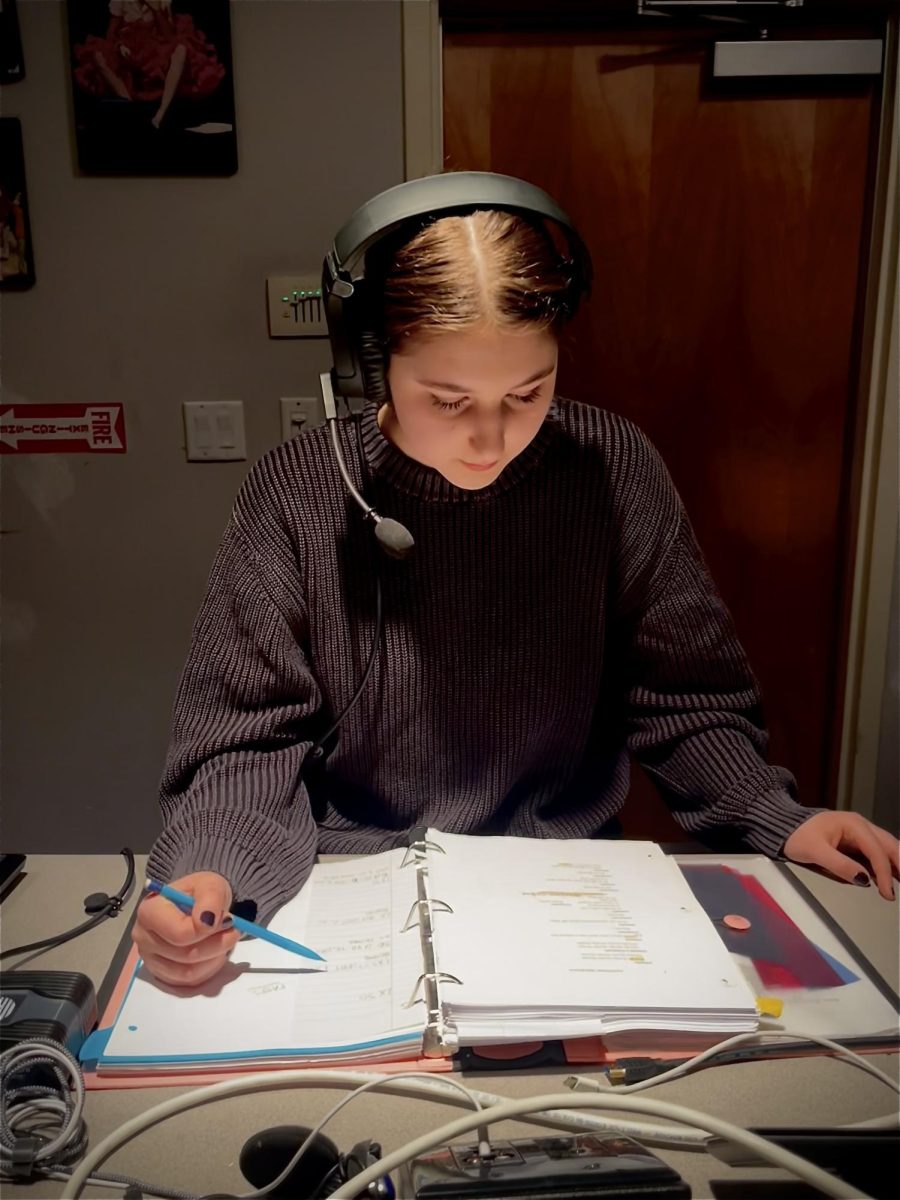

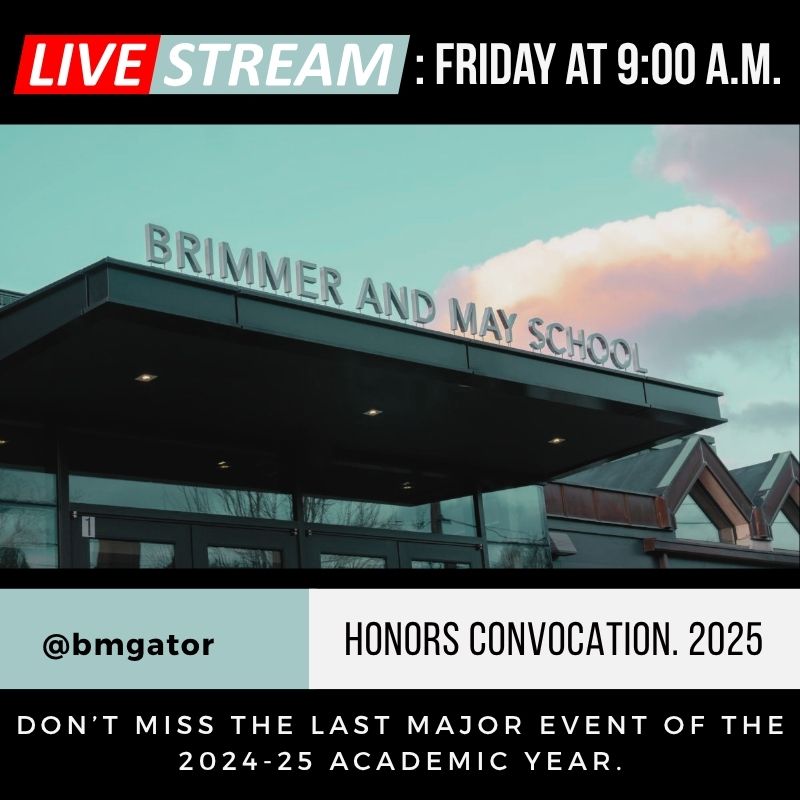

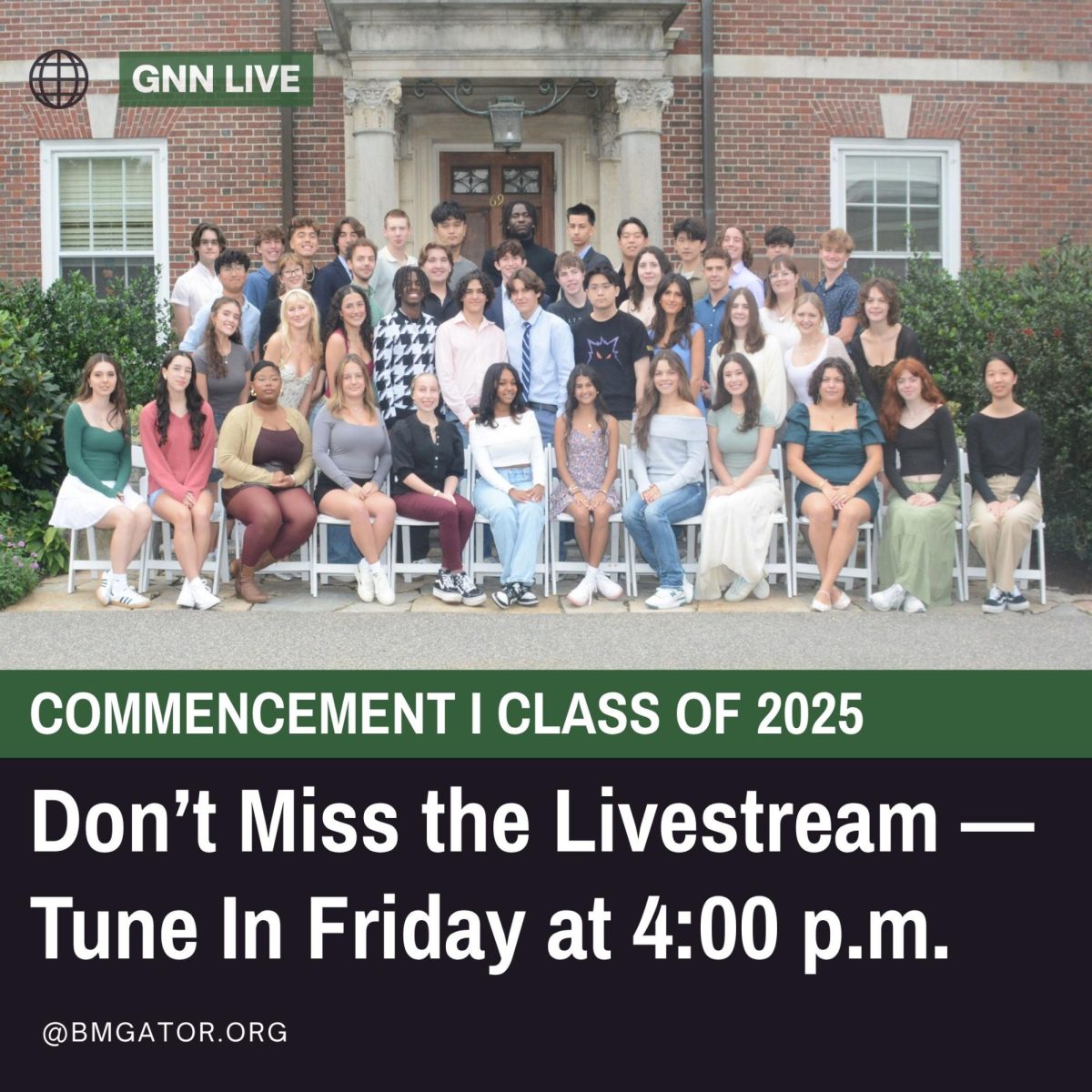

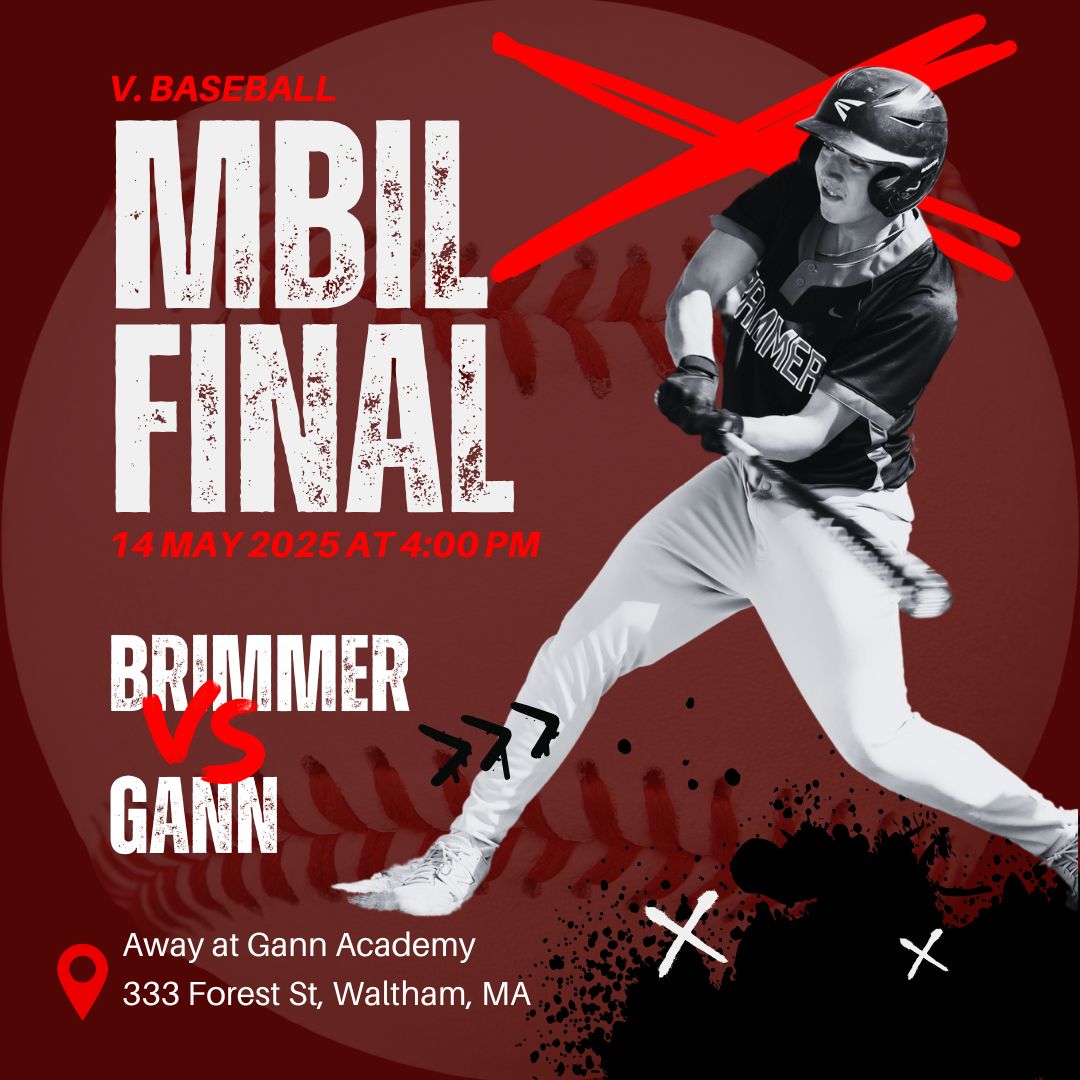

- The right adviser. I advise The Gator, the award-winning student newspaper of Brimmer and May in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, where the average high school grade size is 35 students. Year after year, the newsroom attracts as many as 18 students—sometimes more. Every school has a teacher passionate about writing, working with students one-on-one and student voice. Find her/him and start to build from there.

It’s important to note that as a matter of law, public schools hold an advantage when it comes to student publications since the First Amendment prevents only government officials from censoring speech. The 1998 U.S. Supreme Court decision Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier played a key role in giving public school officials more authority on some school-sponsored student publications while also requiring officials to show reasonable educational justification before they censored material, according to the Student Press Law Center.

While Hazelwood grants too much power to public school administrators, private school students have no level of protection from censorship. For these young journalists, the best course of action might be to convey how curtailing free speech contradicts a school’s mission statement and philosophy.

To assist independent schools in supporting student journalism and publications, I recently launched the Private School Journalism Association to provide links, articles and resources, and attempts to serve as platform for educators to connect and share ideas. This is the first organization of its kind, and I’m hopeful it will begin to fill a gaping hole.

To make my case for student journalism at private schools, I spoke at the Columbia Scholastic Press Association’s spring conference at Columbia University in New York. For my address, “Confronting Private School Struggles with Student Journalism,” I focused on how our respective institutions value an engaged citizenry, leadership, and ethical thinking—ideals most school mission statements share.

“These are healthy values that we should be proud of holding, and I can think of no better way to live up to them than by supporting independent student journalism,” I told the group. “Communities thrive when they are transparent, and censorship is antithetical to who we are and what we stand for.”

Editors’ note: David Cutler ’02 advises The Gator.