Guest Column: My Experience On and After 9/11

Photo illustration purchased from BigStock.com.

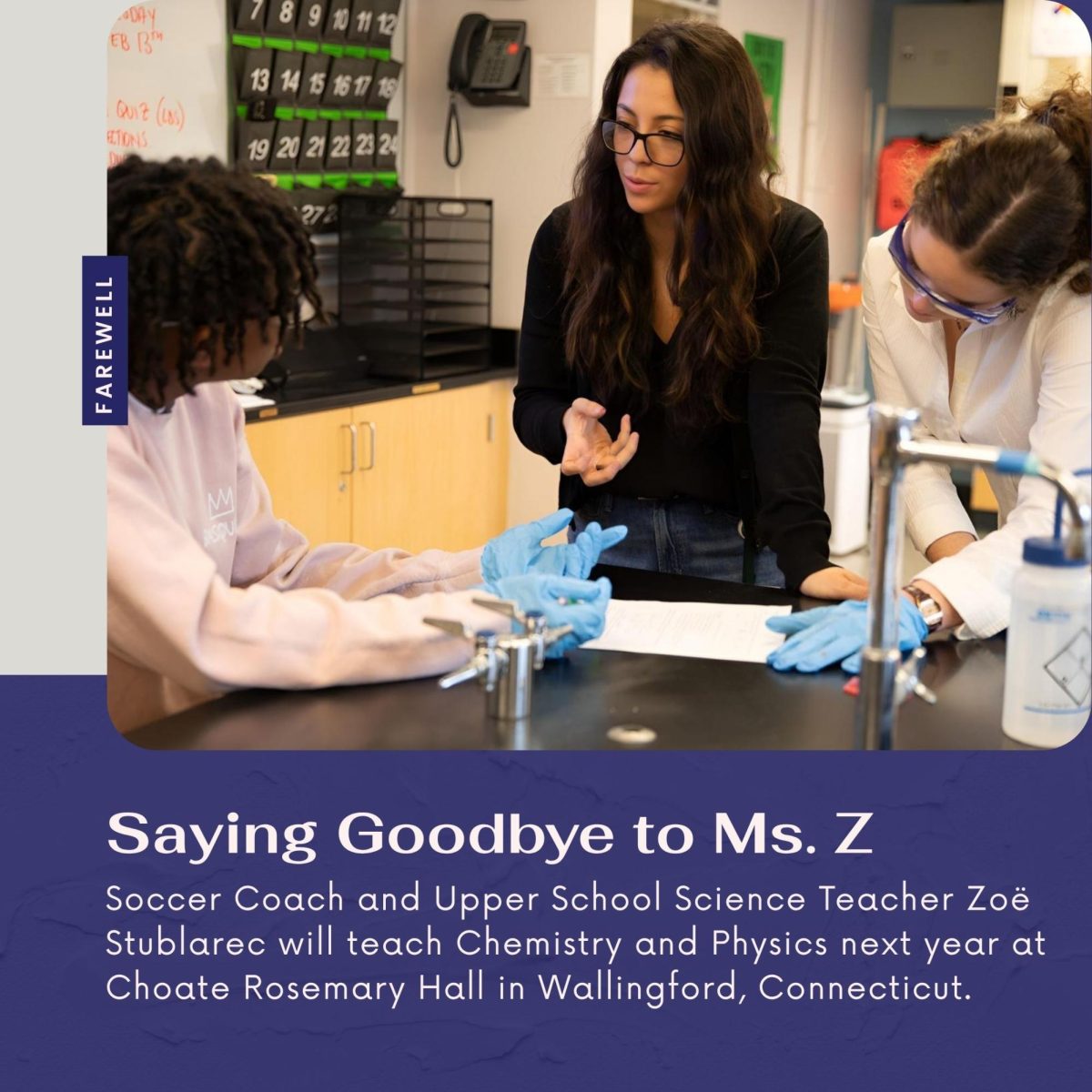

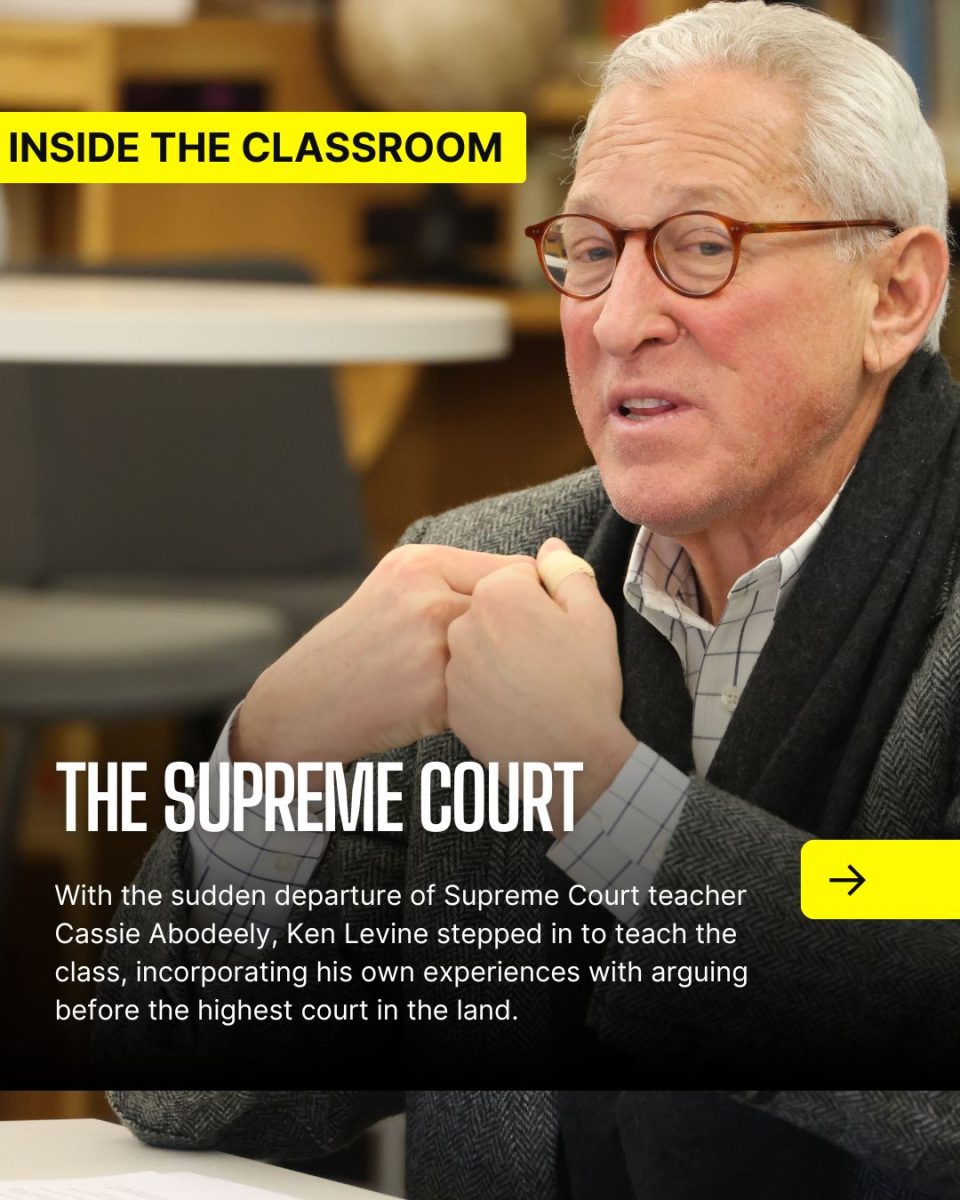

During the September 11 Commemoration on Monday, Director of Summer & Auxiliary Programs Cassandra Abodeely recounted her experience living in New York City during the 2001 terrorist attacks. Abodeely shared her written remarks with The Gator, which are published in full below.

Tuesday, September 11, 2001 was the most beautiful September day—sunny, warm, and bright.

Getting out of the shower, I heard the phone ring. It was my best friend Whitney, who lived down the block from me. “Turn on the TV,” she said.

We sat on the phone together and watched as the first tower burned, and the news anchor reported that a plane had flown into the World Trade Center.

Several minutes later, we watched as the second plane flew into the other tower. “I hope they are not Arabs,” I said to Whitney. I am Middle Eastern, and anti-Arab sentiment had been growing in the US.

We watched until the towers fell. Whitney screamed on the other end of the phone.

As the news anchor tried to make sense of what was happening, he reported that the City was under attack and that other monuments might be next. I hurried off the phone because I wanted to find my sister who worked at Madison Square Garden, which sits above Penn Station, the historic train station in Manhattan.

Phone signals were jammed. I could not get a hold of her.

I ran two blocks over to my friend Eric’s house, hoping he was home because he worked at 100 Centre, less than a block from the Towers. There was no answer.

A couple of hours later, the apartment buzzer rang. It was Eric. He came in and was shaking. “I was running late today because I had to take my car in,” he said. “I should have been there.”

A few hours later, my sister showed up at my door. She was running late to work, and when she arrived, they sent everyone home. Transportation wasn’t running so she had walked the 50 blocks from her job to her lower Manhattan neighborhood. Police had blocked the entrance to lower Manhattan, and she was not allowed in because she didn’t have proof of her New York City address. She still had her New Jersey driver’s license from high school. So, she had walked another 120 blocks to my apartment on the Upper East Side.

I was a few weeks into my first year of law school, and school was closed indefinitely. On September 11, no one knew when things would reopen.

Feeling like we wanted to do something, anything, my rugby teammates and I convened the next day to volunteer at St Vincent’s Hospital. “St. V’s” was the downtown hospital that had fixed many of our broken bones and patched our bloody knees and dislocated shoulders and would be receiving the survivors. Beds were set up outside the hospital, prepared to take in the wounded. Doctors and nurses stood ready and eager.

No one was brought in. There were no survivors. Those who did not make it out on 9/11 did not make it out at all.

Instead of helping at the hospital, many of us ended up volunteering to collect supplies from our fellow New Yorkers who were looking for a place to give. I’m not sure how it all happened, but I ended up co-running a collection site at Public School 41 where we housed EMTs from all over the country who had grabbed their medical bags, hopped in the car, and driven to New York City with no other plan than a desire to help; we collected extra pairs of work boots and work gloves and N95 masks to deliver to the frontline workers who were literally picking through three stories of burning building rubbish to find anyone they could.

“The Pile,” as the remains of the tower were called, was hot and melted the boots of the workers.

On the third day, Doug* showed up. He was a large, loud Sargent from a military base in NJ. He had a camouflaged Humvee and three fellow servicemen. They wore fatigues and told us that they were there to help but had effectively taken the Humvee against orders to stand down because they couldn’t just sit there and do nothing.

Using their military credentials, we packed up the Humvee and a few of us jumped in and rode down to Ground Zero. For the next four days, I was there giving out extra boots, and gloves, and masks, and doing anything else I could do to support the firefighters, police, EMTs, ordinary New Yorkers who worked on the Pile. When I slept, it was on the floor of a burned-out building, somewhere between the Pile and the Hudson River. To this day, I still don’t know exactly where I was. It was so disorienting. I’ve tried to figure it out on countless walks on the Hudson in the intervening years. Everything was covered in thick gray ash.

On my final day at Ground Zero, FEMA rolled in. I had never heard of FEMA, but they came with trailers and flak jackets that said FEMA and radios and told us to go home. Civilians were no longer needed. I rode back uptown in the Humvee. I walked the 89 blocks back to my apartment. And for the first time since that beautiful Tuesday morning, I laid down on my bed and cried.

The next day I went back to school.

Doug and I talk every year on September 11. He’s the first call I make on that day.

*Editor’s Note: Doug’s name has been changed to protect his privacy.