Op-Ed: What is a Superhero?

September 23, 2019

Since the genre’s conception in 1938, with the publication of Action Comics #1, superhero comics have all but bled into society’s collective unconscious. The once fledgling industry, long since perceived as childish at best and stunting or corrupting at worst by the public, has gone on to irreversibly alter the fabric of popular culture across the globe.

Come the 21stcentury and the seemingly unstoppable juggernaut that is the Marvel Cinematic Universe, housing some of the highest grossing films of all time, the myth is almost impossible to ignore—the likes of Iron Man and Thanos being as well known as Bill Gates and the World Cup.

But all of this just begs the question: What is a superhero, and how have they continued to resonate with audiences for almost a century.

The default answer to the former would probably fall somewhere under the umbrella of ‘enhanced samaritan; spandex optional,’ most notably Stan Lee himself, but that really doesn’t do the job justice. Anyone with a hero complex, a chip on their shoulder, or the ability to dent steel could go out and try to fight the good fight, but if that’s all you got going for you, you’re more likely to fall somewhere between ‘unregistered vigilante’ and ‘suicidally reckless’. It takes more than just a costume and the capability to be a hero, otherwise we’d just end up in a landscape à la Kingdom Come.

When you peel away Superman’s seemingly unlimited power and his status as the flagship superhero, you’re left with… a guy.

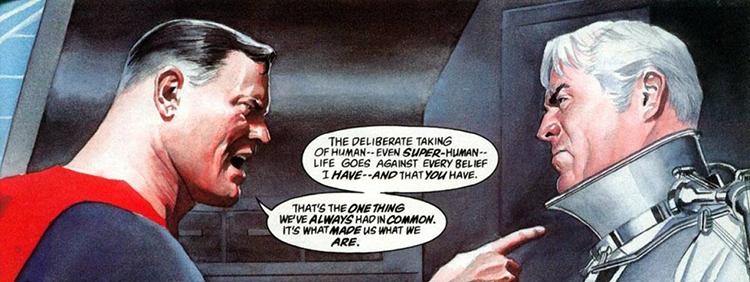

In their magnum opus, Mark Waid and Alex Ross depict a world with a seemingly endless well of superhuman might—straight out of the Dark Age of comics. Powerful and ambitious heroes are in no short supply, contrasted with a drought of ethics and self-restraint. Major cities become war zones for capes, distinction never given to who’s on what side of the law because it doesn’t really matter. Both parties care more about the fight and their own goals than the mortals they swore to protect. Notably, it takes the return of Superman—the original heroic ideal—to set them straight, and even then, drastic measures have to be taken from all parties involved to resolve the conflict in any meaningful way.

So, is Superman, the unyielding pillar of justice, the template for a good superhero? Yes and no. In many respects, DC’s patron saint is the ideal: unwavering, unstoppable, uninteresting. That’s not to say he isn’t a good character, far from it, but when you peel away his seemingly unlimited power and his status as the flagship superhero, you’re left with… a guy.

Unlike most other heroes, Superman doesn’t have a defining moment that sets him down the path of heroism. Rather, he had a handful of small moments that would have irreversibly changed the universe should something had changed. His will to help, even if natural, was cultivated over several years spent living among a family that enshrined American core values in their very being.

This is reinforced by a young Clark Kent finding the Fortress of Solitude, and hearing a message from his deceased Kryptonian father about being the world’s savior. Clark Kent became Superman because the entirety of his life cultivated him for that very moment. If Kal-El had crash-landed in, say, the slums of Gotham, things would have turned out very differently.

That’s not to say that the Man of Tomorrow’s mold should be completely scraped. Heroes, true heroes, have come from simpler circumstances. Heroes like Shazam and Green Lantern were explicitly given powers with the express purpose of helping people and went on to do so. The Fantastic Four and Hulk suffered freak accidents that did nothing for their morality and decided to fight the good fight anyway. There was no hesitation once they got their powers under control. They saw that they had been given unimaginable power and decided to do right by it.

So, what separates these heroes from the later generations in Kingdom Come that would rather the world burn than they lose? Simple: compassion.

At some point in their lives, they knew what it was like to be mortal. To be helpless in a world where the only thing standing between you and the countless threats that plague the pages of these stories are a handful of heroes. They know what it’s like to be afraid. To be frustrated. To be alone in a world you know will never be truly safe.

But like hell they aren’t going to try to make a difference.

To be a superhero means being able to do incredible things in extraordinary circumstances. It means having an adamantium grip on your more unsavory urges, for the sake of public safety if not your current punching bag. It means balancing your ego and self-esteem in a world that treats you as a legend first, weapon second, and a person third.

Above all, to be a superhero is to be human. Human in the sense that you know what will happen if you and yours fail a world on the brink of chaos. Even if you have no mask, money, or might to your name, that’s a lesson that resonates and inspires across the ages.

Editors’ note: In April, Eisner-winning comic book author Mark Waid spoke with Charles Beagle’s Popular Culture in American History class, taught by Gator adviser David Cutler. This story was updated Thursday, May 14, to include the podcast below.